Great Lakes Exhibit

This Great Lakes Collection, along with works by other Great Lakes photographers, was originally on display at Waldo Library, Western Michigan University, Kalamazoo, Michigan.

(For the Artists' Statement, please scroll down to bottom of this page.)

ID_6674-6C2_06

Palisade Head —

Lake Superior

The human footprint on the earth is so large, our population so dense, that the human heart and soul ache for places that restore a sense of perspective and balance.

ID_37-4074C

Freshwater Power

The lakes still have an appetite for unfortunate boats. Lake Superior claimed the Mesquite in 1989. More recently Lake Michigan swallowed a barge. Freshwater waves are steeper and closer together than saltwater waves, giving a foundering boat less time to recover before being hit again.

But there are friendlier meanings and metaphors rolling about here. A small boat with an efficient, sea-kindly hull and secure hatches and rigging is buoyed and boosted along almost playfully by the waves. Canadian naturalist Mike Jones gave us this advice for traveling in big water: "Just remember you're a cork on the water and paddle with grace.”

ID_4-3497C

Open Horizon — Lake Michigan

To be on a Great Lakes sand beach at sunset is to be a child at peace with existence in a marvelous world bounded by open horizons.

Photographers' Note: The star-shaped reflections on the water highlights are not photographic special effects. No special filter or computer manipulation was involved. They are the result of light waves passing through, and being bent by, a narrow opening (about f22) in the lens. This is very visible evidence in the "macro" world of the wave nature of light, and evidence of the interaction of the quantum world with our everyday existence.

ID_36-5508C

Oiseau Point — Lake Superior

Oiseau Point in Canada's Pukaskwa National Park rises from the depths of time. This nearly three billion year old metamorphic rock was originally exposed at the surface before life covered land, when erosion proceeded at rates unimaginable today. It was subsequently buried so deep that it was heated and metamorphosed into beautiful and intriguing patterns. Through the eons, it was uplifted and then scoured and polished by glaciers. To walk on this shore is to literally stroll into the deep, deep past.

During a two-week sea kayaking trip along this coast, one of us steadied the kayak while the other leaned over almost to the point of immersing an ear. Water motion, and no place for a tripod, necessitated a high shutter speed. A tilt and shift lens on the camera (usually used for slow, careful composition on a tripod) was shifted down to gain on almost-in-the-water perspective; the lens was then tilted to extend the plane of focus further than the required aperture for this shot would normally provide. To succeed, all lifeforms must be inventive and adaptable, even the lowly photographer.

ID_18-4715C

Agawa Rock, Lake Superior

At least 117 pictographs, estimated at 500 to 3,000 years old, grace the cliff at Agawa Rock, described by archaeologist Thor Conway as "the equivalent of a Stonehenge, a one-of-a-kind, regionally important concentration of past spiritual activities." This sacred site evokes a sense of awe and reverence; many visitors instinctively respond to its power and "natural spirituality." As the Conway points out: "Rock art sites can be understood as one portion of a larger spiritual landscape."

The rock paintings in the foreground are of giant serpents called Chignebikoog, and Mishi-Peshu, a lynx-like creature of Ojibway lore with horns on its head and spines on its tail. "Mishi-Peshu represents a bold abstraction of Lake Superior's power and fury," according to Conway. "In many ways, Mishi-Peshu is the ultimate metaphor for Lake Superior — powerful, mysterious, and ultimately very dangerous."

ID_36-7297C

Sunrise over Tall Ship Madeline

Manitou Passage, Lake Michigan

The schooner Madeline sailed the Great Lakes more than 150 years ago; a historic replica was built by the Maritime Heritage Alliance of Traverse City, Michigan. Sailing at sunrise in Lake Michigan's Manitou Passage, this tall ship is a visual echo of a time in the 1800s when the Great Lakes were highways, islands were bustling places of business, and the mainland was still mostly roadless wilderness.

ID_38-566C

Approaching Storm, St. Joseph North Pier Lights — Lake Michigan

In 1842 Francis Count de Castelnau wrote of a Lake Michigan storm: "I have seen the storms of the Channel, those of the Ocean, the squalls off the banks of Newfoundland, those on the coasts of America, and the hurricanes of the Gulf of Mexico. No where have I witnessed the fury of the elements comparable to that found on this fresh water sea."

With ocean-class storms — but less maneuvering room before encountering the mainland, islands, reefs, or peninsulas — Great Lakes shipping had an elevated need for aids to navigation. Before radar, Loran, and GPS, that meant lighthouses. The result was the world's greatest concentration of lighthouses, well beyond 300 United States and Canadian stations.

ID_36-980B

Niagara Falls

The combined waters of Lakes Superior, Michigan, Huron, and Erie thunder over Niagara Falls, a natural wonder that has awed and fascinated people for centuries. In 1678 Father Hennepin described Niagara Falls as: "...an incredible Cataract or Waterfall, which has no equal." In the 17th century, the Great Lakes and their connecting waterways were the major transportation route into the interior of the continent. Niagara Falls presented an enormous obstacle; the all-important portage around Niagara Falls was the entrance to the watery highways of the Great Lakes.

The Niagara River drops 330 feet on its way from Lake Erie to Lake Ontario. At Niagara Falls the river plummets over the erosion-resistant limestone of the Niagaran Escarpment — a vertical drop of as much as 167 feet. But erosion-resistant is a relative term as the falls erode upstream toward Lake Erie by as much as five feet a year.

ID_2430C2_04

Mackinac Bridge,

Straits of Mackinac

Lake Michigan and Lake Huron join in the Straits of Mackinac, separating Michigan's upper and lower peninsulas. The Mackinac Bridge arches five miles across the Straits, gracefully linking the two peninsulas.

The Mackinac Bridge was opened to traffic in 1957, after three years of construction. Between the two main towers of the bridge lies an ancient riverbed. A river once flowed here through a steep canyon during a time of extremely low water levels as glaciers retreated from the area. At the midspan point of the bridge, the water plunges to a depth of 295 feet and motorists drive along at a height of 199 feet above the water's surface.

ID_32-1622C

Boldt Castle, St. Lawrence River

At the east end of Lake Ontario, nearly 2,000 islands are congregated in the Thousand Islands area of the St. Lawrence River. Here lake freighters traveling the St. Lawrence Seaway thread their way from the Great Lakes out to the Atlantic Ocean.

Nestled among these islands, the spires and turrets of a castle rise above the treetops of Heart Island. At the turn of the 20th century, George C. Boldt, owner of the Waldorf-Astoria Hotel in New York City, had a castle built on Heart Island — complete with turrets, a drawbridge, and an underground passage. The 120-room mansion was modeled after a 16th century Rhineland castle and designed to be a gift for his beloved wife, Louise. When she died suddenly, George ordered the work to be stopped, and he never returned. For 73 years the castle stood vacant, until the Thousand Islands Bridge Authority acquired the island in 1977 and restoration of the deteriorated castle began.

ID_16-4667C

Flowerpot Island — Lake Huron

Part of the Niagaran Escarpment, the Bruce Peninsula extends into Lake Huron, forming the western shores of Georgian Bay. The tip of this peninsula is surrounded by Fathom Five National Marine Park, which includes Flowerpot Island. The sea stacks, called "flowerpots," are monoliths of layered sedimentary rock that have been eroded and sculpted by wind and waves over the millennia.

ID_30-7766C

Great Egret in Breeding Plumage, Lake Michigan

Many birds seek islands for breeding. Here they find isolation and protection from predators. Nesting islands can be raucous places, full of a variety of birds. This great egret's neighbors on its Lake Michigan nesting island included gulls, cormorants, herons, and pelicans. The egret's breeding plumage includes graceful plumes ("aigrettes") on the back that extend beyond the tail. When these long plumes were extremely popular for use in women's hats, the egret's population declined severely.

ID_36-953C

Lake Erie Storm, Fairport West Breakwater Light

According to the United States Coast Pilot: "Weather can make navigating the Great Lakes a pleasure, a challenge, or a terror...The Great Lakes lie in the midst of a climatological battlefield, where northern polar air often struggles for control with air from the tropics. During spring and autumn, the zone separating these two armies lies over the Lakes region." Truly hair-raising storms, the kind that end up in Gordon Lightfoot ballads, most often occur in fall when the water's stored heat energy rapidly intensifies approaching low pressure systems.

Lake Erie is the shallowest of the Great Lakes, with an average depth of only 62 feet (compared to Lake Superior's average depth of 483 feet). On such a shallow body of water, waves build rapidly when winds sweep across the lake.

ID_23-3547C

Sleeping Bear Dunes —

Lake Michigan

The dunes that drift along Lake Michigan's eastern and southern shores form the largest expanse of freshwater dunes in the world.

"To walk in the dunes is to walk through time. These miniscule grains of quartz that gather together to make such a magnificent community were created long before the coming of humans. Children of the glaciers and wards of the wind, they have for millennia washed and drifted, bounced and tumbled from one age to the next....Ancient sands continue to wash and drift into dunes along modern Lake Michigan. And long after we are gone, the sand will still be here, or there, or somewhere, ever shifting and drifting. These sands of time have a profound effect on visitors, connecting them with the timelessness of the elements and the natural processes....Life in the dunes is hard, sharp-edged, and real. Sand stings the face, bringing a pleasantly painful reality — there is no buffering from life here, no numbing of the senses from false overstimulation. There is no tolerance for pretense and wasted energy; what is important and real is evident, what isn't is quite literally blown away. The dunes are a place of great struggle, of individual and community interdependence. The metaphors and analogies blowing through these rolling wilds are too insistent to be ignored. Just as members of the foredune communities make life possible for the downwind communities, so do we humans need each other — and all of creation."

— excerpt from Wild Lake Michigan

ID_27-5563C

Caught in a Gale, Lake Superior

"Rushing down the face of one wave, the bow would plunge into the trough and then rise with the next wave as water swirled around Ann's sprayskirt.... Occasionally the entire boat was awash for seconds that ticked into brief eternities, and then finally it would rise again like a calm and confident creature of the sea....Wave crests were beginning to fly off with the wind...water washed over hatch covers and swirled around sprayskirts, spray flying back and splattering against rain parkas and faces. As the entrance to Old Dave's Harbour neared, a feeling of giddy thankfulness came over us — thankfulness for the experience, thankfulness it would soon be over....The little protected harbor was almost calm as we drifted, surging gently up and down while wind and wave hammered the outer shore...we unpacked the weather radio; after spitting out the usual garbled static and fuzzy, mangled voices, it said: 'a gale with sustained winds in excess of 35 knots...'

To paddle Lake Superior in a gale wasn't a personal battle against the lake; it wasn't the macho struggle against nature's wildness that is so often manufactured by adventure writers. It's just what happens sometimes out here. Venturing out on the largest freshwater sea in the world requires that we commit ourselves to the perils as well as the pleasures of the journey. This isn't a virtual reality world; the experience can't be turned off when it becomes too real."

— excerpt from Lake Superior: Story and Spirit

ID_2933-35C2_05X

Mackinac Island — Lake Huron

One of the best-known and most visited of Lake Huron's islands is Mackinac Island, famous for its horse-drawn carriages, Grand Hotel, and fudge shops. In the 1880s visitors came to the island by lake steamer; today over a million people visit Mackinac Island each year, most of them arriving by ferry. But beyond the bustle of downtown and summer's crowds, the island still offers wildness and solitude. In late October at Arch Rock, we took in a beauty founded 4,000 years ago when the much higher waters of ancestral Lake Nippissing sculpted a limestone shore that is now a high cliff with an ancient sea arch.

ID_36-5225C

Lake Superior Coast —

Pictured Rocks

In a mere 40 miles, Lake Superior's coast at PIctured Rocks National Lakeshore features cliffs, waterfalls, beaches, Northwoods, lighthouses, shipwrecks, inland lakes, and sand dunes atop high banks of glacial deposits. Along rock-bound Lake Superior shores, water is contained by Superior's rocks, in turn shaping the rocks in a visual microcosm of the basin-wide interplay between rock and water that defines Lake Superior.

ID_36-6601C

South Bass Island

Sunset — Lake Erie

South Bass Island is part of an archipelago forming a stepping-stone path across western Lake Erie; geologists believe that the Lake Erie Islands once formed a larger, continuous peninsula when lake levels were lower in the wake of receding glaciers. Now separated by the waters of Lake Erie, the island chain reaches from Ohio's Marblehead Peninsula to Ontario's Point Pelee, serving as rest stops for migrating birds and monarch butterflies. Some of the islands are also significant resting places for vacationing humans.

ID_6746-8C2_06

Morgan Falls —

Chequamegon-Nicolet

National Forest

The history of the upper lakes basin is one of geological upheaval involving rifting, volcanism, tectonic collision, and glacial scouring. The modern day result is a tortured and fractured landscape, colonized by an adaptive and inventive life process. Erosion resistant rock still juts and protrudes through this living carpet, giving flowing water an exciting ride on its way back to the lakes.

ID_39-2887C

Moskey Basin Rainbow,

Lake Superior

This rainbow was the culmination of a series of alternating storms and rainbows that passed over our Moskey Basin campsite, with each rainbow more brilliant than the previous one. It was a powerful day and a powerful experience, revealing much about the magic of water — the solvent and substance for the existence of all known life. It buoys our vessels and our spirits, while revealing the hidden multi-spectrum nature of ordinary white light.

ID_26-5422C

Snowcoast, Apostle Islands National Lakeshore

Lake effect snow is created when warmer moist air from the lakes is blown over land where it cools, and precipitates as snow. Although this seems normal and unremarkable to those who live in snowbelts around the lake, lake effect snow is really rather unique. Weather and Climate of the Great Lakescomments: "Lake effect snowstorms are also unique in their lack of occurrence in most other areas of the world...other than the Great Lakes area of North America, they occur only along the east shore of Hudson Bay in Canada and along the west coast of the Japanese islands of Honolulu and Hokkaido."

This scene was taken while backcountry camping in Apostle Islands National Lakeshore. The horizontally frozen ice on the birch trunk hints at a recent strong storm off the lake. What can't be seen is how deep and powdery the snow was, rendering snowshoes marginally effective and making the shortest hike with camera and tripod a major physical undertaking.

ID_3-1922C

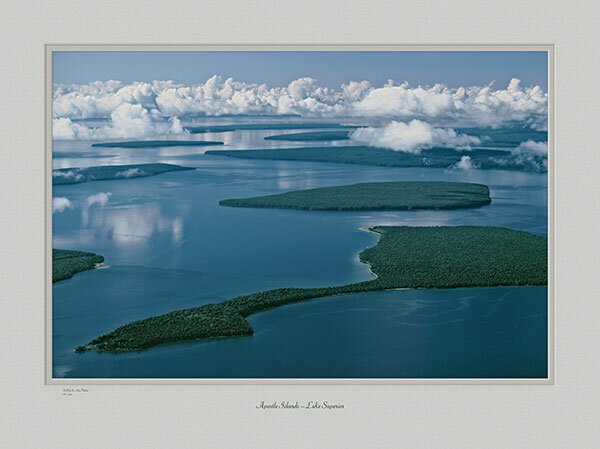

Apostle Islands — Lake Superior

"On warm summer afternoons, coastline and nearshore areas are usually at least 4-8 degrees (F) cooler than the interior....This temperature moderation is carried further inland on the summertime lake breeze. As sun rapidly heats the land, air begins to rise, drawing cooler humid air in off the lake. This moist air is in turn warmed and rises until cooling and condensing at higher altitude. The resulting 'lake-breeze front' is often marked by a stationary line of puffy cumulus clouds, or occasionally, a light but steady rainfall. Islands experience this phenomenon from every direction. Often on calm, sunny summer days, each of the Apostle islands is mirrored in the sky with its own uniquely shaped billowy cloud."

— excerpt from Lake Superior: Story and Spirit

ID_1072C1_03

Great Lakes Aurora

Of all the ephemeral natural wonders, the active aurora is one of the most compelling and majestic, as well as elusive. What seems like a surreal, "out-of-this-world" experience is just that — an aurora's origins are 93 million miles away, on the sun. From that giant fireball of thermonuclear reactions, swirling hot gases and twisting magnetic field lines, a solar wind constantly blows charged particles into space. After a 3- to 4-day journey traveling more than one million miles per hour, these high-speed particles strike Earth's magnetic field (magnetosphere), where the high-speed electro-interaction results in electrons accelerating down magnetic lines into Earth's upper atmosphere where they slam into oxygen and nitrogen. These atoms and electrons become ionized and excited, emitting the light of the "auroral ovals" that normally hover above the North Pole (aurora borealis) and South Pole (aurora australis). Light from these collisions covers a wide spectrum from infrared to ultraviolet.

When sunspots (areas of concentrated magnetic activity on the sun's surface) are active, with more frequent and intense eruptions of energy called solar flares — the solar wind gusts intensify and push the auroral ovals toward the lower latitudes. It is then that familiar night skies in the Great Lakes area are transformed by glowing rays, undulating curtains of light, and beams pulsing so actively that we can almost feel the energy in the heavens.

Slow and patient time spent under the northern lights has a wonderful way of bringing us in touch with the wonders of the nocturnal world. Loon calls echo across the water, owls hoot in the distance, and a moose splashes as it wades nearby. In such moments time seems to stand still.

ID_5986C2_05

Water Lilies — Northern Michigan

Wetlands are amazingly productive and valuable ecosystems, critical for fisheries, flood control, water cleansing, and a whole host of critical ecosystem functions. But the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service has reported that "on average the lower 48 states have lost over 60 acres of wetlands for every hour between the 1780s and the 1980s." The U.S. National Academy of Sciences pegged the acres of lost wetlands at "approximately 117 million acres, or half the original total, by the mid-1980s." "Lost" is a misnomer. We didn't lose them. We destroyed them. They continue to be drained, dredged, and filled in at the rate of approximately 300,000 acres per year — 20,000 acres per year in the Great Lakes Basin.

It is now known that wetlands are effective and cheap water treatment systems and can also tremendously reduce flooding and its immense resultant human misery. Wetlands are not waste places waiting to be put to better use — they are better use.

ID_26-3301C

Loon and Chick,

Sylvania Wilderness

Family Values — the real thing, not the political football — are not unique to human beings. With loons, each parent shares equally in nesting and rearing the chicks. Over much of the summer, loon chicks are taught to feed and care for themselves by attentive parents who will put themselves in harm's way to protect their children. This ancient bird species is a living testimony to the durability and effectiveness of the family as life's most basic social unit.

ID_7183C1_04

Pitcher Plants and Cranberries, Stockton Island Bog

"It's a tough life for a plant, making a living in a bog. Acid water, little oxygen, hardly any nitrogen from minimal biological decay — and all of this compounded by cold water that makes absorption of the minimal nutrients even more difficult." (These conditions also inhibit plant decomposition, tying up significant quantities of carbon dioxide that would have added to global warming.) "But what bogs lack in biological diversity, they more than make up in imagination and adaptability — a testament to nature's ability to pour life into the most inhospitable places." Pitcher plants turn the tables on the animal world, reversing roles from dinner to diner. "Insects are attracted by a sweet liquid secreted at the edge of the leaves. Downward pointing hairs lining the inside...prevent insects from climbing out. As they take the easy route downward, insects become increasingly plastered with sticky platelets — and finally tumble into the enzyme-rich liquid to be digested into a nitrogen-rich bug soup."

— includes excerpts from Wild Lake Michigan

ID_4754C2_04

Chimney Bluffs, Lake Ontario

On Lake Ontario just east of Sodus Bay, New York, a natural marvel rises out of the depths of time. A remnant from the Ice Age, Chimney Bluffs are eroded drumlins — glacial-drift landforms whose orientation indicates the direction of glacial movement. Over the ages, wind, rain, and Lake Ontario's wave action carved the ancient drumlins to their core, leaving high sharp-edged ridges, pinnacles, and spires. In the undeveloped Chimney Bluffs State Park, hikers follow the shoreline, or a footpath along the edge of a wooded bluff, for a multitude of views reminiscent of scenes from "out West."

ID_28-2926C

McCargoe Cove Moose,

Isle Royale — Lake Superior

Lake Superior envelopes the remote Isle Royale archipelago of over 400 islands. Isle Royale's moose-wolf study is the longest running research project of its kind in the world, and the mystique of moose and wolves attracts visitors to this wilderness island national park. But we soon become immersed in the sights, sounds, smells, and rhythms of life in the natural world. In the process, we intuit that we are all on a shared path with our fellow creatures.

On this shared path, what does the future hold for the Great Lakes and their inhabitants, in a world facing global warming — an increasingly thirsty world where water is viewed as a commodity to be bottled and sold? From a biological perspective, life-sustaining freshwater is not a commodity. It is a necessity. From an ethical perspective, it is an inalienable right of all lifeforms.

ID_29-4655B

Manitoulin Island Sunrise, Georgian Bay

Northern Lake Huron encompasses more than 30,000 islands, including the world's largest freshwater island, Manitoulin. From Manitoulin Island's eastern shore stretches Georgian Bay, the largest freshwater bay in the world — sometimes referred to as the sixth Great Lake. Manitoulin Island curves across northern Lake Huron as part of the Niagaran Escarpment, a dolomitic limestone escarpment that arches through the Great Lakes as the backbone of such landforms as Niagara Falls, Lake Huron's Bruce Peninsula and Lake Michigan's Door Peninsula.

ID_1641C2_04

Calypso Orchids, Isle Royale

A body of water is only as healthy as its surrounding watershed. The natural state of most of the Great Lakes watershed is to be forested. A healthy forest can be gauged by its diversity of tree species and tree ages — but it can also be gauged by its ground cover, especially flowers. Orchid expert "Frederick W. Case, Jr., writes: 'At present the Great Lakes region is especially favorable to orchids because of its geographic position, its lake-influenced climate, its soil types, and its glacial history. Fifty-eight orchid species grow natively in the region...This region surpasses all others in temperate North America, except Florida, in the number of its orchid species.'

Nearly all trees, grasses, shrubs, and flowers are connected to a vast underground mycorrhizal community. Mycorrhizae (myco=fungus, rrhizae=roots) are symbiotic combinations of fungal filaments...and the roots of higher plants. Mycorrhizal fungi break organic matter down into bite-size compounds and molecules; in addition, they physically link up with plant roots, extending their nutritional reach and efficiency far beyond the usual limits. Nitrogen, phosphorus, and other food molecules are brought in by fungal hyphae from distant sources — a kind of nutritional superhighway. Besides nutritional aid, these fungi confer to their rooted partners a greater resistance from drought, disease, and soil acidity....For all its hard work, the fungal partner in this joint venture receives approximately 10 percent of the host plant's photosynthetic production of sugars and other carbohydrates...Few mycorrhizal fungi fare well on their own....

Studies have shown a five-fold increase in growth of conifer seedlings with a healthy complement of mycorrhizal fungi, as compared to seedlings with few root fungi...European research has shown that intensive forest management [harvesting trees on short rotation] reduces the normal complement of 30 to 40 species of mycorrhizal fungi associated with a tree's roots to just 3 to 5 species."

So why are flowers, especially calypso orchids and other lady's slipper orchids, such good indicators of forest health? Because they have very limited, rudimentary roots and will not survive without mycorrhizal fungi. The presence of these orchids indicates a healthy soil mycorrhizal community.

— includes excerpts from Lake Superior: Story and Spirit

ID_1125C2_04

Loons in Morning Mist,

Lake Superior

"The common loon is the avian world's deepest diver, with recorded dives beyond 200 feet in the Great Lakes. Pressures encountered at such depths require strong, solid, non-buoyant bones. A loon is as heavy as a bald eagle, but with half the wing surface. Consequently, it is a heavy-bodied flier, requiring approximately one-quarter mile of open water for a runway. But it also penetrates deeply into humanity's earliest beginnings, and beyond. Many people have an intuitive affinity for loons. Their haunting vocalizations pluck a vaguely familiar and resonant chord in many of us; perhaps this is because of our long history together. Loons are the oldest known living bird species, somewhere on the order of 80 million years. The sight and sound of loons accompanied the entire evolutionary span of our human ancestry."

— excerpt from Lake Superior: Story and Spirit

ID_27-6349B

Sea Lamprey

There are over 180 aquatic exotic species in the lakes, from bacteria to sea lamprey. Many of these uninvited and unwanted guests are courtesy of the Welland Canal, which allows shipping to bypass Niagara Falls and lock up into the upper lakes. Those exotics that couldn't make the trip on their own hitched a ride on freighters: in ballast water, on hulls, locker chains, etc. Some were introduced by accidental spills. The sea lamprey probably muscled its own way through the canal, quickly spreading to all the upper lakes, wreaking havoc on the native fish population, especially lake trout.

Once a sea lamprey attaches its suction disc mouth to its victim, the rasp-like tongue keeps the meal coming. Each lamprey destroys 40 or more pounds of fish in its lifetime. Various methods, especially lampricides, have been used to reduce lamprey populations. But once an exotic species is established, there is little to no hope of eradicating it. The hard truth is that large manmade changes to the ecosystem usually result in equally large and negative unintended consequences.

ID_23-5752C

Stromatolites, Lake Superior

"Rocks on Superior's north shore are full of the ancient story, harboring fossilized remains of Precambrian microbial life. The discovery of fossils in these stromatolites was the first hard evidence of life's incredible antiquity. What look like giant Cheerios embedded in the rocks are actually cross-sections of dome-shaped mats of cyanobacteria and algae that lived in the Animikean Sea covering this area two billion years ago. They lived in a carbon dioxide atmosphere; free oxygen was poisonous to them . But their newly evolved version of photosynthesis released oxygen into the environment as a waste product. The combined effect of these tiny puffs of pollution altered the atmosphere, forever changing the course of life on Earth.

Just as their tiny individual piffles of pollution combined to cause global changes eons ago, even minute amounts of persistent toxic chemicals pose severe dangers today. this is why the 1978 Great Lakes Water Quality Agreement between Canada and the United States called for zero discharge of persistent toxic substances.

The fossilized microbes in these rocks chronicle the profound and lasting effects primitive life had on Earth's atmosphere, and on the course of life itself. By example they speak to us about our own present day effects on the biosphere. It all seems so incomprehensibly long ago. But the inhabitants of two billion year old stromatolites were once as real as we are now. Like them, we are the future's ancestors, determining what kind of world our progeny will inherit. Unlike them, we have knowledge and choice."

— excerpt from the program "Lake Superior: Story and Spirit"

ID_2847-51C2_05 and ID_7729-31C2_06

Choices We Make

In a healthy Northwoods forest, Trailing Arbutus is a classic ground cover. But forests are being replaced at an alarming rate by uncontrolled growth, and especially by the pernicious exotic ground cover, Creeping Pavement. There is an awful lot of it: less than two percent of land in the contiguous 48 states is designated wilderness. More land in this area is under pavement than protected as wilderness. Creeping Pavement is extremely difficult to eradicate. and it removes all of the life-sustaining functions of the natural systems it replaces.

A leading environmental science textbook, Living in the Environment, estimated the benefits in dollars to a community for 50 years of one tree's function: oxygen production/carbon dioxide removal, air pollution reduction, soil replenishment and erosion control, fish and wildlife protection, water retention and cleansing, etc. A tree does this 24/7, 365 days a year, for free. It would cost $196,250 for us to provide the beneficial and necessary functions of one tree. Creeping Pavement and uncontrolled growth eliminate all these life-sustaining functions while speeding up water runoff, polluting water, and contributing to global warming not only by eliminating carbon dioxide removal by trees, but by radiating back stored heat at night. One Michigan drain commissioner considers sewer grates to be the new headwaters source for the Great Lakes.

It doesn't have to be this way. We can make better, smarter choices. For instance, New York City is paying one billion dollars to protect watersheds around its reservoirs. The city determined that a treatment plant to provide just the water retention and cleaning that was being done for free by forests would cost 8-9 billion dollars.

What is required, and what is happening, is a fundamental world view change. World view changes are serious business, involving backlash from the old world view. Researchers Paul Ray and Sherry Ruth Anderson document in The Cultural Creatives, with hard data, that there is a huge and unprecedentedly rapid world view change taking place right now. Hard data shows that humanity is moving from a mechanistic to an ecological world view, from meaningless consumption to meaningful connection, from getting more to becoming more, from inactive pessimism to active and realistic optimism. In essence, we are moving from fragmentation to wholeness.

Great friction results from the clash between dying and aborning world views, because when our world view changes, our choices change. The race is on between accelerating consequences and accelerating world view change with corrective choices.

Artists' Statement — John and Ann Mahan

As the world's largest freshwater ecosystem, the Great Lakes shatter all our usual tiny concepts about lakes. A short list of superlatives includes:

Less than 1 percent of all water on Earth is in freshwater steams, rivers, wetlands, lakes, and groundwater: 20 percent of this rare and precious freshwater resides in the Great Lakes.

The Great Lakes are bounded by over 10,000 miles of coastline, encompass 35,000 islands, and are nourished by over 200,000 square miles of watershed.

They provide drinking water for over 30 million people in 2 countries.

They hold the planet's: largest lake (by surface area — Lake Superior); largest freshwater bay (Georgian Bay); longest stretch of freshwater dunes (eastern coast of Lake Michigan).

They sustain at least 46 species of animals and plants unique on the planet, plus 280 species considered globally rare, including the world's largest concentration of Ram's Head orchids.

The Great Lakes are the focus of international agreements that are the first of their kind in human history: the Boundary Waters Treaty, and the Great Lakes Water Quality Agreement with its ecosystem perspective.

They remain dynamic and active: white pelicans began breeding in the basin during the last decade; "internal waves" and currents travel at depths up to 1,000 feet in Lake Superior; Earth's crust is still rebounding from the last glaciation, rising at Lake Superior's north shore at a rate faster than any active North American mountain range.

But there is a compelling intimacy in all this gee-whiz bigness. While experiencing firsthand the power of these inland seas can be awesome and overwhelming, living with their ever-changing moods and energy instills patience and flexibility. Encounters with their diverse community of lifeforms remind us that we are on a shared path with our fellow creatures. Slow time spent cradled in this unique life-system makes clear that matter and meaning are part of the same whole reality, as we begin to connect on a very personal level with that extraordinary and essential sense of Other, and with the parallel sense of belonging that resonates quietly throughout the natural world. More than anything else, this is what captivates us; this wholeness is what we seek to convey in our work.

To measure the Great Lakes' physical dimensions is simple math and science. But to measure their value and meaning requires a much more sensitive instrument, the human psyche. And it is an inherently subjective process. That should come as no surprise; our most respected physicists tell us everything is contingent and interdependent with everything else, that there is no reality independent from everything else.

Artistic and scientific modes of inquiry and expression are inherently incapable of a so-called "objective" rendering of the world. They are limited to two or at best three dimensions in a very multidimensional world, and they are subject to the selections and interpretations of the observer. No paint palette, film, or sensor can contain the huge dynamic range of light and color "out there." The human behind the instrument selects what to focus on, and where in this compressed reality to place and interpret the subject. Scientific bias, subjective choice, artistic vision, call it what you will — but no human recording of what's "out there" is ever completely objective. The human brain appears to have evolved as an organ to select out what to pay attention to and what to ignore, and then make sense of what is subjectively selected. When done honestly and faithfully, we glimpse reality.

This is what our writing and photography is about: we strive to honestly and faithfully represent and convey the marvelous and soul-sustaining subjective reality that we interact with in the Great Lakes ecosystem.